Here we go again. The topic I chose was:

Question 2: Using case studies from animation history, examine how these animations may have

contributed to the discourse of cultural imperialism (Tomlinson, 2001).

Paula

Acknowledgements and preface

Not part of the essay, but I would appreciate if you read this.

In this essay, I will go into topics of Cultural Imperialism, providing my analysis and critique. Then I will examine a western animated film – The Lion King, and analyse as well as hypothesise how it might have affected the discourse of cultural imperialism within the academia, and what effect it had on the world itself.

Before that, it is important to understand the question, and it did leave place for speculation:

Using case studies from animation history, examine how these animations may have contributed to the discourse of cultural imperialism.

Interpreted literally, the question asks how the field of cultural imperialism research has been affected by certain animations, or where they shifted the discussion. Another interpretation is how these animations affected the world through cultural imperialism. I will try to touch on both, but will mainly follow the first reading.

It is with regret that I have to say, that the format of this essay does not allow for a very deep analysis of the topic, even for a meta review. With that, I have opted for a single case study, and dedicate space to establish the framework for what cultural imperialism means. Even John Tomlinson’s book (Cultural Imperialism: A Critical Introduction, 1991), which is so rich in nuance, and rejects aggressively-tones articles of the day in favour of said nuance, leaves room for doubt and interpretation. I do not hope to overshadow his research by any means, but merely point to a direction in which I feel he might have expanded and should have paid more heed to.

Overall, I hope to convey the basics of cultural imperialism, and summarise the discussion in its context surrounding one animation – Disney’s Lion King.

I would like to acknowledge that there are more interesting topics to be discussed – like the “cultural imperialism in USA and USSR – Tom & Jerry vs Nu Pogodi,” for instance, was my initial draft title. Among other topics, this would allow me to discuss the Schiller and the generic models, and US- and non-US-based imperialism. But due to scarce research into these animations in this context, I could not possibly provide a meta-analysis within the word count.

I hope that with this, my choice of topics will seem reasonable.

Table of Contents

- Cover Page

- Acknowledgements and preface

- Table of Contents

- What is Cultural Imperialism?

- The case of Lion King and Media Imperialism

- Analysis and summary

- Bibliography

What is Cultural Imperialism?

The terms Cultural Imperialism, and even Media Imperialism – are often contested. For example, one study gives a definition:

[…] the hypothesis of cultural imperialism suggests (1) that the program contains a message, (2) that such a message is received, consciously or not, (3) that it is in the hegemonic interest of the multinational power, and (4) that it is in the active disinterest of the receivers.

(Katz and Liebes 1990)

In contrast, David Rothkopf (In Praise of Cultural Imperialism? Effects of Globalization, 1997) denies the last assertion – whereas the former acknowledges “the active disinterest of the receivers,” Rothkopf suggests that we can and should shape the message to benefit the receivers, as well as the source power.

John Tomlinson says that the term Cultural Imperialism is ill-defined. Tomlinson goes forth to break the concept down into four issues: (1) media imperialism, (2) discourse of nationality, (3) critique of global capitalism, (4) critique of modernity – which are, respectively – (1) how cultural pressure is delivered and applied, (2) the effects of said pressure, (3) economic aspects of the issue, and (4) an analysis of the global dynamics which cultural imperialism plays into (Tomlinson 1991). However, the core problem of clashing definitions remains.

I will attempt to bring my research together to create an inclusive characterisation, which also includes the larger context and a bigger picture (consider Figure 1).

Global inter-cultural interaction

Assertion: cultural imperialism is a small facet of a very large set of processes – the global inter-cultural interactions and struggles. These interactions can be analysed from two angles:

- in their own right, as natural processes with their own laws.

- in the context of who causes it, and whether it is intentional, and whether it is for good or ill – as radical scholars examine it.

Let me explain my rationale. First, we need to establish two concepts for the definition to take hold.

Akin to Atmosphere and Lithosphere on Earth, and the purported Noosphere in thought, there are several “spheres” in global human society – including power relations, the economic sphere, and the cultural sphere. All of them are intertwined, but also live their own, separate lives.

To give an analogy – stock and currency trading. There is a dichotomy in predicting stock prices, not too different from the light’s wave/particle duality, or even more in line with Leibniz’s Pre-established harmony theory (The Monadology, 1714).

On the one hand, stock prices are governed by real-world events – war, elections. With culture, we can see it as a result of economic and power struggles.

On the other hand, one can predict stock prices purely by looking at the graph (value over time) – because it seems to live by its own laws of causality. The mystery is that these laws happen to coincide with the events of the real world (Figure 2). This is to describe that processes on massive scales seemingly have a life and laws of their own. As much as culture is shaped by politics and war, it has its own abstract laws that govern it – and both seem to coincide.

The other concept to consider is that of memetics (Dawkins, 1976). Dawkings argues that the world consists of entities, the aim of which is to survive, through replication and/or persistence. It can be an image macro that you see on the internet, the concept of washing hands before food, or it can be a whole culture[1]. A successful image macro is one that keeps getting used, a successful culture is one that prevails over survivalist challenges – be it famine, flood, war, or enemy propaganda. It is culture that develops mechanisms of response that bring either doom or prosperity to its people. So, it is not that cultures always willingly clash in competition – it is not their intention; but in retrospect, this turns out to be precisely what the surviving ones did – try to dominate.

As such, most cultures strive to dominate even when territorial and economic disputes are settled. Some manage to achieve harmony and symbiosis, but those are rare examples – just like in nature.

This brings me to my conclusion:

What Dawkins says, and what we see from the example of stock markets, is that cultures are entities that (un)wittingly compete for survival, and they can be viewed as living by their own abstract laws, or – within radical schools of thought – as direct products of human endeavour.

Thus, we establish the concept of “inter-cultural struggles”.

These struggles exhibit themselves through cultural pressures and exports, physical and intangible:

- Diplomatic is one method through which culture proliferates, where countries willingly exchange traditions and art, for instance (exhibitions, festivals).

- Imperialism coerces subjected nations into new culture – through physical force.

- Cultural Imperialism is another method of cultural interactions, different from the one above – and we will consider the difference further below.

Cultural Imperialism

Whereas prior, a country’s borders were a (somewhat controllable) entry point for both physical and cultural threats, now, with the advent of satellite TV and now Internet, defending borders has become increasingly futile in preventing foreign cultural influence. (Ang, Desperately Guarding Borders, 2001)

Cultural Imperialism spreads elements of a nation’s culture to other regions. When it is effective, the receiver incorporates elements of a foreign culture into theirs in a fragmented fashion, causing inorganic divides between generations, loss of national identity and country’s direction. On the other hand, it can provoke a sort of a cultural renaissance. (Ang, 2001).

Today, entertainment is the prime means for delivery and Bathes’ Myth is the what conceals the payload. This side of cultural imperialism does not imply a political hierarchy – Japan can influence the US as much as the other way around. Often it is suggested that it would be the nation in a higher position that exports its culture – and herein lies the problem of not considering the term “cultural imperialism” within the wider context of cultural struggles for survival and dominance. Tomlinson argues (1991, p. 173) that it is due to no physical coercion that a culture is imposed in today’s age. Indeed, if coercion took place, we would be dealing with traditional imperialism. The term itself – cultural imperialism – implies an “empire” to be present, but it needn’t be physical. A “cultural empire” is, in fact, what we are dealing with. And the pressure that it might exert is no coercion – in its pure form, it is more akin to a temptation.

Another vehicle for cultural imperialism is tourism and business relations – and here it is usually the more successful country that affects the less fortunate. The image in this case is that of wealthier, well-off tourists visiting a poorer nation, inspiring images of success – a businessman in a suit and tie, or a rock star in leather jackets.

This all serves as a vehicle to inspire changes of lifestyle and ideals in the affected regions. From the obesity epidemic that sweeps the world, to McDonald’s ubiquity, to the western body image and fashion ideals – all of this can be observed throughout the world, even in regions where such entities would be ill-expected or suited.

Countries with weaker cultural identities are affected, or those which are not well-off in other ways – economic and social mostly. A promise of a land where everyone is well off and is not restricted by their government is very appealing to nations suffering from food shortages or political oppression. (Ang, 2001)

The case of Lion King and Media Imperialism

Importance of animation

To consider the relevance of Lion King, one must realise the relevance of Disney, and animation.

Where earlier, culture was passed down in the form of folklore and then literature, primarily from parents to young children, with the advent of television the role of the storyteller shifted onto the entertainment industry, especially family animation.

TV shows, broadcast around the globe, with wide demographics, provide fertile material for discussion of cultural imperialism. However, family media, with a narrower audience, might be more crucial for analysis. Let’s examine an assertion by Walt Disney, as quoted by Henry Giroux:

I think of a child’s mind as a blank book. During the first years of his life, much will be written on the pages. The quality of that writing will affect his life profoundly.

(The Mouse that Roared: Disney and the End of Innocence 2001, p. 17)

To take the idea to its natural conclusion, here is a quote more eloquent than I could have put it:

[Disney’s power] begins with the children, for whom Disney’s products are so powerful; they teach life’s lessons (think of Pinocchio’s nose) and they build dreamscapes. Children grow into adults, who are fond of Disney because it shaped the way they think about the world.

(William F. Powers, The Washington Post, 1995)

Children then grow up with (Disney’s) dreamscapes, formed in the US. How will they shape their countries? What if the storyteller ceases to be the parent, and becomes a foreign corporation, who might not even be aware it is preaching to this culture in the first place?

Here we can already see where the academic dialogue might shift. We start talking about futures, aspirations, and ideals – those that kids will try to implement in their societies after they grow up. These core tenets of the psyche are not as easily changed in adults, which is why with Dallas we considered more subtle influences.

On Disney and Lion King

But why Disney? In combination, a perhaps greater effect is had collectively by broadcast cartoons, from Sponge Bob to Samurai Jack. However, individually, Disney’s films are heavy hitters. They present more material per case study, providing better representation of animation as a whole.

One of the earliest Cultural Imperialism discussions about Disney was a book-essay called How to Read Donald Duck (Dorfman and Mattelart, 1971). The authors asserted Disney’s deliberately twisted worldview – centring on money, lack of agency, imperialism – but not overtly – through Myth. For example:

Disney relies upon the acceptability of his world as natural, that is to say, as at once normal, ordinary and true to the nature of the child. His depiction of women and children is predicated upon its supposed objectivity, although, as we have seen, he relentlessly twists the nature of every creature he approaches.

(Dorfman and Mattelart, 1971, p. 41)

It is important to remember that Disney’s rise to relevance was through propaganda animation for World War 2 (Smoodin, Animating Culture: Hollywood Cartoons from the Sound Era, 1993, pp. 71-95) and Latin America (Smoodin, Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom, 1994, pp. 131-180). So, at the very least, Disney had experience in that department. Were their later works in the same key? If not, could they have used the tools acquired from drawing propaganda, unconsciously?

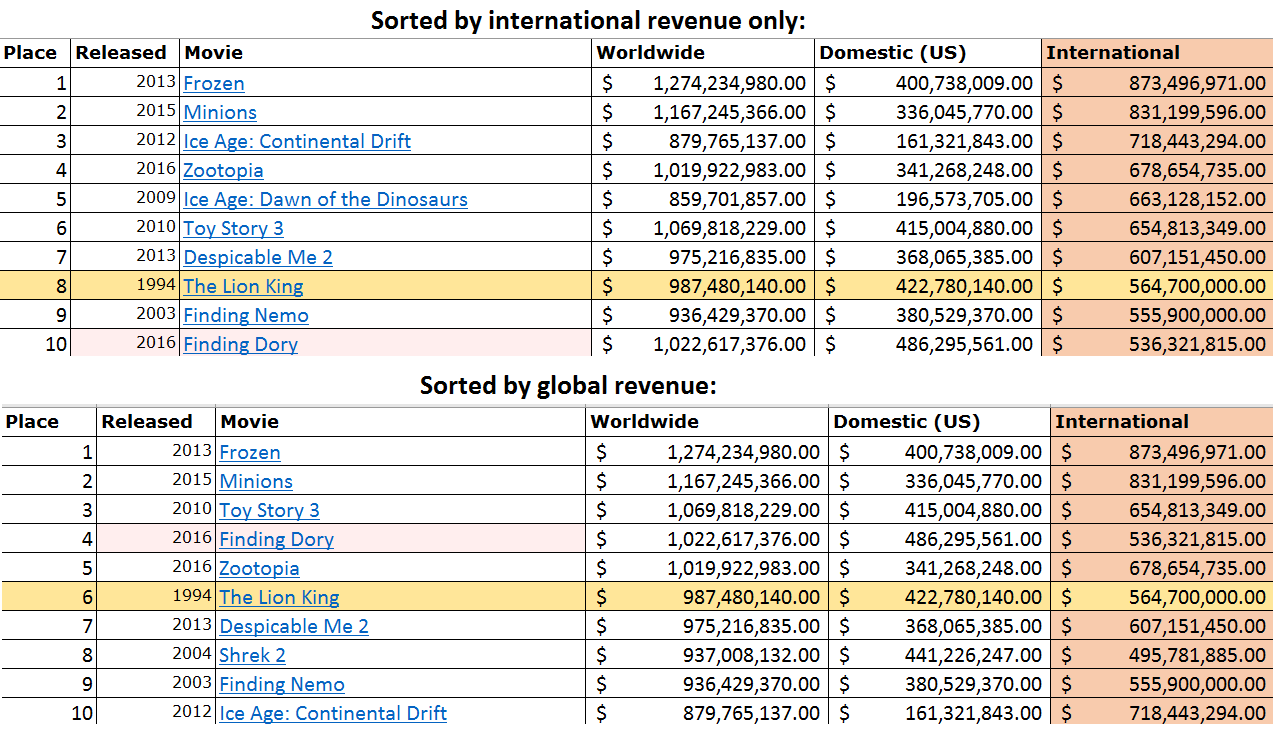

Of all Disney animation, the Lion King is the most popular pre-2000 animation. Today it remains #8 highest grossing animation in non-US markets (Figure 3). Meaning it affected children all around the globe even before the internet, and has most research surrounds it. Furthermore, Lion King was subject to various cultural critiques.

With all that in mind, let us examine it. Could this animation have affected a family watching it in Taiwan? Will it contribute anything to the society in Kenya? Finally, where could it have swerved the discussion about cultural imperialism as a whole?

Western negative stereotyping

Manuel M. Martin-Rodriguez (2000), re-worded in the book Animating Difference, compares the hyenas’ depiction to the Latinos, while Lee Artz to that of black youth:

[Lion King] is better read as an effort to engage and work through the competition and conflict associated with Latino migration northward, an allegory that restabilizes the white core through a story about lions and hyenas in an invented Africa.

(King, 2011)

[…] those uninitiated to certain stereotypes can acquire a Disney-based social template to judge future social interactions: upon hearing a group of black teens talking in a shopping mall, a white toddler was heard to exclaim, “Look, mom, hyenas!”

(Artz, 2003, p. 3)

These two claims that Disney purports discrimination are but the tip of an iceberg. Even though already we see that the accusations seem to clash, this does not make them invalid. In this case, another book reconciles the argument simply by saying that some hyenas are depicted black, and some Latino – based on voice acting (Gooding-Williams, 2006, p. 38). But, we would not even require that. As a famous saying goes, beauty is in the eye of the beholder; and if such is the nature of beauty, we can rest assured as to the nature of its opposite. But then the question is, what eye hold the Moroccans, the Nigerians? What will they see through their own cultural lenses?

In their work Interacting with “Dallas” (1990), Katz & Liebes arrive at a conclusion: people view foreign shows through their own culture’s lens (quoted in Tomlinson, 1991, p. 48) – a group of Arabs misinterpreting an episode to fit their worldview being the prime example. So long as the stereotypes are not overt, there is always an issue of symbolism in cultures – do the Nepalese have a stereotype of “a jobless black man” that the hyenas might allude to? Or is it exclusive to USA, created during Reagan’s campaign, to give a (probably wrong) example?

These issues need to be considered on a per-culture basis.

In a similar study, Ien Ang (Watching Dallas: soap opera and the melodramatic imagination, 1982) also concurs the notion, albeit differently – viewers might be aware of negative conotations of a film, but choose to ignore them (as in the case of Dallas and the culture of consumerism). Is the case different when the Myth is less overt?

Again, this is open to discussion that is outside the scope of this essay. So far, the criticism and academic studies surrounding the subject have only presented accusations, but did not examine them in the context of cultures other than the US’, as happened with the show Dallas.

The essay The Lion King’s Mythic Narrative (Ward, 1996) swaps Barth’s Myth for Jung’s. Having said that, this essay is not the best example of the author’s strengths as an analyst and researcher – to which her book Mouse Morality (2002) is a testament. Just like the above, the essay fails to justify its assertions – it merely states them. Nevertheless, we have a contrasting view. Ward cited an article that in turn cited a Disney spokesperson:

“They [the critics] are people for whom the very word ‘black’ has racist suggestions. They sniff out [discriminations] where no reasonable person would ever suspect they existed”.

Terry Press (Ward, 1996, quoted on p. 5)

To reinterpret, Disney’s position is that the critics are trying to see something that is not there. There could be a long discussion about the validity of those claims, and about the role of intent in Myth, and we would probably not arrive at a consensus even after engaging with neuroscience. But, me might not need to, considering the findings of Ang, Katz, and Liebes.

Social order

Disney did not get far with its portrayals of social hierarchies since Donald Duck, an essay argues:

Nothing is resolved until the preferred social order is in place. No one lives happily ever after until the chosen one rules. All is chaos and disorder in the pride lands until Simba returns as monarch.

(Artz, 2003, p. 9)

The author asserts this as an “essential Disney’s law”. This is also supported by Dorfman & Mattelart (1971, pp. 36, 42, 96).

The assertion is that Disney proliferates an idea of a specific social order, in this case a monarchy. While it would be dubious to assume that it is in Disney’s interests per se, we should consider the implications in third-world countries. What of those that might be dependent on the US financially or politically? This might be to Disney’s benefits, as its media empire makes money all over the globe. As always we should remember that Disney as a company is still borne of capitalism and of US culture.

Dancing to USA’s tune

One research of Kenya’s tourism and culture touches on the phrase “Hakuna Matata” and song “Kum Ba Yah”. They were parts of the regional culture for century. Then, after the former was used in Lion King and the latter in America in general, we saw a change:

Africans have taken a phrase and a song originating in Africa and have performed it for the tourists with a New World Caribbean reggae beat. […] “Hakuna Matata” and “Kum Ba Yah,” have been widely interpreted in American popular culture as expressions of “Africanness” and “blackness,” and then have been re-presented to American tourists, by Africans, in Africa.

(Bruner, 2001, pp. 892-893)

Although the paper puts this in a positive light, there is room to discuss all the implications. At the very least, the US’ sheer influence forced the locals to change their own ways and culture to accommodate an image created outside their country. This is precisely cultural imperialism at work – much muddier than the simple good or bad, but influential, and rather one-sided. If a simple animation, seemingly innocuously, can have a country change its inner cultural flows, we should be very concerned of the (un-)intended consequences of the whole clumsy US (and Western) media giant.

Analysis and summary

Contribution to the discourse of cultural imperialism

There not being many studies about animations and cultural imperialism per se is unfortunate, but correctable. Let us examine what the discussions on media and cultural imperialism focused on before:

Watching Dallas (Ang, 1982): What causes the pleasure of watching? Does the Mythical element play a part? Text as an interaction, not a one-sided process.

Interacting with “Dallas” (Katz and Liebes, 1990): Does the viewer separate the “primordial” and the American? Text as dialogue (mirroring Ang’s study). The clash between values makes foreign viewers reflect on their own culture, not blindly accept Myth. Elements of the Myth still smoothing out concerns about power differences (“the rich are also unhappy”).

How to read Donald Duck (Dorfman and Mattelart, 1971): Analysis of impact of values in Disney comics. Imperialist Myth, Disney’s colonial attitudes, product consumption. The person behind the media and his influence.

Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom (Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto) (Smoodin, Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom, 1994, pp. 181-201): A reversal – considering Cultural Imperialism is a tool, weapon for the USA, the essay discusses how Japan consumed and aimed that weapon back. “To whose benefit is the presence of Disneyland in Tokyo?”

The discussions were deeply psychological, insightful, critical. With criticism of contemporary animations, there is a noticeable shift: from talking about larger societal implications, towards talking about specific racial, sex, and class issues. Undeniably important ussies in many parts of the world, but an ironic example of Americentrism and Eurocentrism – as those issues are the main topic of discussion there, but are far from the only topic relevant to Disney in Africa or Asia.

This is in part because there are few essays. Is the topic of cultural imperialism losing its attention from academia? Is the West too preoccupied with its problems to worry how it affects the less fortunate countries? Doubtfully.

But an undeniable trend surfaced – there are fewer essays, and near to no academic studies. The discussions of The Lion King, and other recent animated film seem to only bring issues up, but not critically analyse their merit or impact.

There is one possible answer to this. The Internet. In recent years, it far overtook the television and cinema as the primary companion of kids and adults, and it brings the cultural homogenisation to its realisation much sooner than the old-fashioned cultural imperialism ever could. At the same time, the internet developed so much of its own culture that it is clear – examining it within the old framework of cultural imperialism is inefficient and restrictive.

At the same time, far more noticeable are the effects of entertainment that comes into the West – like Japanese Anime and Korean pop music and drama series, which seem to have fan bases in every culture across the globe. Perhaps the researchers would be paying more attention to these issues, as whether they are more important than western media imperialism or not, they are new phenomena. So perhaps the reason to this lack of deep research is not due to the dimming interest or neglect of the topic, but due to the shifting realities and social issues.

PS: this was based on a case study of Lion King, which I assumed to be a prime representative of animation of its age. It is possible that it is not the best-suited case study, but to analyse that, further, deeper research would be required.

Bibliography

Note: the formatting and content got messed up when copying from Word. If you’re interested in the bibliography, I suggest you reference the PDF attached at the top of this page. Thank you.

- Ang, Ien. 1982. Watching Dallas: soap opera and the melodramatic imagination. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij SUA Amsterdam.

- —. 2001. “Desperately guarding borders: media globalization, ‘cultural imperialism’ and the rise of ‘Asia’.” Chap. 1 in House of Glass: Culture, Modernity, and the State in Southeast Asia (Social Issues in Southeast Asia), edited by Yao Souchou, 27-45. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Artz, Lee. 2003. “Animating Hierarchy: Disney and the Globalization of Capitalism.” Global Media Journal 1.

- Brokerages & Day Trading. n.d. “How To Use Fibonacci Retracement In MetaTrader 4.” Brokerages & Day Trading. Accessed May 21, 2017. http://www.brokeragesdaytrading.com/article/7669125545/how-to-use-fibonacci-retracement-in-metatrader-4/.

- Bruner, Edward M. 2001. “The Maasai and the Lion King: Authenticity, Nationalism, and Globalization in African Tourism.” American Ethnologist 28 (4): 881-908.

- Dawkins, Richard. 1976. The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press.

- Dorfman, Ariel, and Armand Mattelart. 1971. How to Read Donald Duck.

- Giroux, Henry A. 2001. The Mouse that Roared: Disney and the End of Innocence. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Gooding-Williams, Robert. 2006. Look, a Negro!: Philosophical Essays on Race, Culture, and Politics. Routledge.

- Katz, Elihu, and Tamar Liebes. 1990. “Interacting With “Dallas”: Cross Cultural Readings.” Canadian Journal of Communication 15 (1): 45-66.

- King, Richard. 2011. Animating Difference: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Contemporary Films for Children (Perspectives on a Multiracial America). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm. 1714. The Monadology.

- Munroe, Randall. 2011. “Standards.” xkcd.com. 20 7. Accessed May 23, 2017. https://xkcd.com/927/.

- Powers, William F. 1995. “Eeeek? Disney is big and getting much bigger. Should we be afraid of the mouse?” The Washington Post. 6 August. Accessed May 28, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/style/1995/08/06/eeeek-disney-is-big-and-getting-much-bigger-should-we-be-afraid-of-the-mouse/b0c03328-25a1-4394-bf79-0a49552adf67/?utm_term=.0cd51e83a067.

- Rothkop, David. 1997. “In Praise of Cultural Imperialism? Effects of Globalization.” Foreign Policy (107): 38.

- Smoodin, Eric Loren. 1993. Animating Culture: Hollywood Cartoons from the Sound Era. Rutgers University Press.

- —. 1994. Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom. Rutgers University Press.

- Tomlinson, John. 1991. Cultural Imperialism: A Critical Introduction. London: Continuum.

- Ward, Annalee R. 2002. Mouse Morality: The Rhetoric of Disney Animated Film. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Ward, Annalee R. 1996. “The Lion King’s Mythic Narrative: Disney as Moral Educator.” Journal of Popular Film and Television 23 (4): 171-178.

[1] John Tomlinson’s book Cultural Imperialism (1991) discusses briefly what people might imply when they simply use the term “culture”. In this case, I imply the collective customs of a people that accumulated over time as a response to environment’s pressures. Nowadays, the customs are indeed more detached from their survivalist purpose, and are more focused on aesthetics and a spirituality. However, even today there is survivalist pressure applied – consider food cultures in various countries, including the USA with its obesity rates and a culture with more refined concepts about food, like Singapore.